Principles

We think differently, that’s our competitive advantage. We dig deeper and we don’t accept mainstream assumptions. We question everything.

The result is a unique philosophy that guides our methodology. It’s a high-conviction strategy that avoids following-the-herd in a relentless pursuit of out-performance.

Our principles

- Buy the right company, at the right price, and leave it be

- Value Calculation to be compared to market not derived from market

- Risk is not determined by size or sector

- Outperformance comes from concentration

- Macroeconomics is unpredictable

- Sustainability is a function of outperformance

Buy the right company, at the right price, and leave it be

We select stocks with conviction, we have complete confidence in our analysis. In the absence of material deviation from our thesis, we give our investee companies time to reach their full potential.

When it comes to investing, we look to Bertrand Russel’s In Praise of Idleness, “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” We believe one must have utter conviction in the strength of analysis and then leave it be. In the absence of material deviation from your analysis, leave your investments to mature as the laws of nature and physics demand. The progression of strategy and market has nothing to do with revolutions of the sun or the end of the financial year. It need not be linear either.

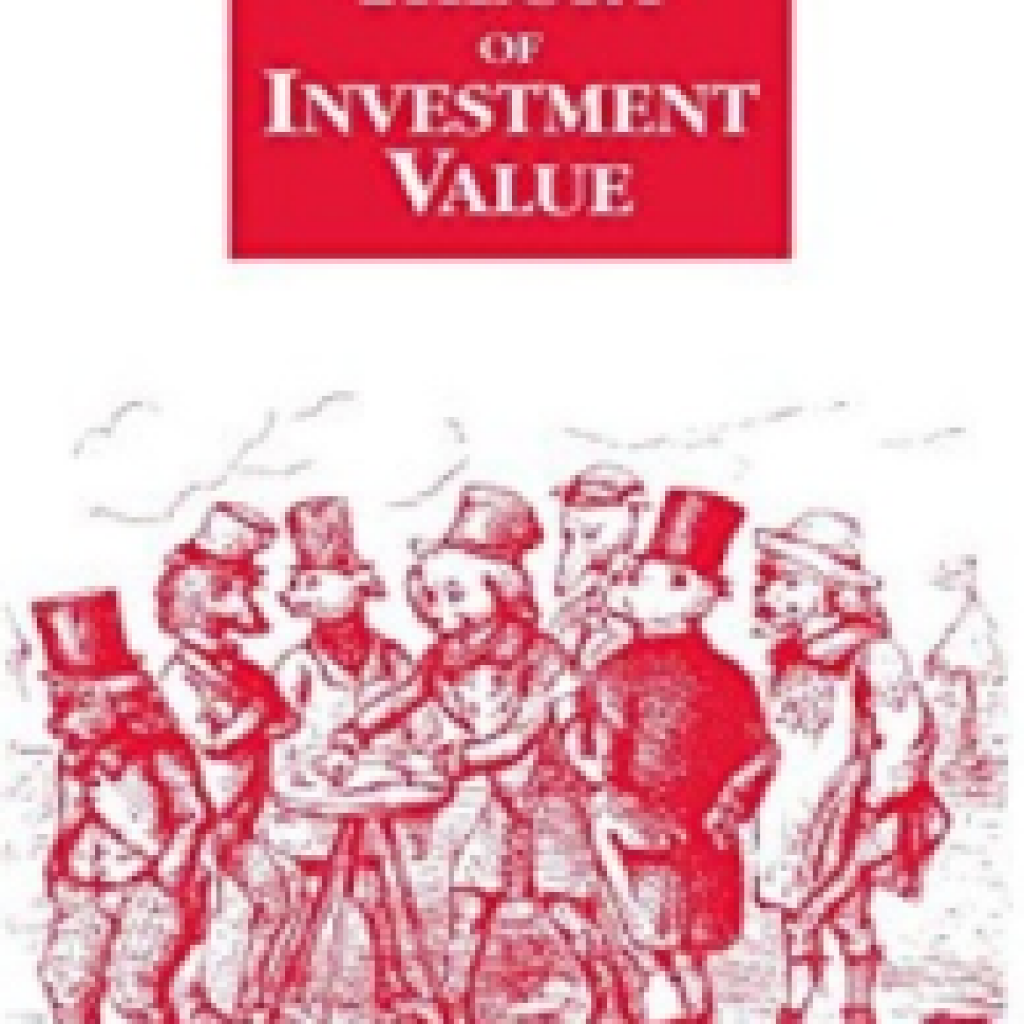

Value Calculation to be compared to market not derived from market

There’s much more to valuing a company than a PE ratio. Valuation is highly subjective, and we don’t agree with mainstream investment methodologies that weigh heavily on risk assessments that are unrelated to core business drivers.

We build a unique financial report for every company we analyse. A company’s financial reports are just a starting point for analysis, not conclusions in themselves. This enables us to derive distributable earnings, so we can compare different business models under the one framework. The method has proven itself over many valuations in many different markets.

One must also be careful as to which business models you choose to make estimates on. When it comes to buying equity in a business, one needs to pay a price that allows for error in valuation. One needs to find business models that have high degrees of probability in their outcomes as determined by the insight of the purchaser.

As Einstein said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.”

Risk is not determined by size or sector

Conventional wisdom says the small-cap is far riskier than the large-cap, we disagree.

We have a long-term horizon, and so short-term movements in stock prices have little relevance. Mainstream convention holds that risk is volatility and beta is a measure of that volatility. For us beta has no place in our assessment of risk.

Broad market movements are not reflective of an individual company’s situation. Even the short-term movements of an individual stock price can vary wildly from the underlying business case.

In our view, the short-term movements of a stock’s market price shouldn’t bear a weighting on the valuation of the underlying company.

Instead, it’s the dynamics of the underlying revenue drivers over a multi-year time horizon that are the key indicators of risk.

We analyse a business model and consider what it might look like in 10 years, and what level of probability we can attribute to that future. It doesn’t matter to us if a small company has short-term volatility along its multiyear CAGR of 40%, as opposed to the perceived ‘less risky’ company producing 5% growth per year.

Consider banking. Conventional wisdom tells us that a young fintech growing revenue at 35% per annum, with profitable cash flow and growing market share, is riskier than holding an established bank. We disagree. Incumbents in the financial services industry are facing powerful forces of disruption and rapidly losing market share. Variance punishes downside and upside.

We focus our thoughts on the fundamentals of the business model and the probability of acceptable returns over the long term. If the probability of acceptable returns looks high, versus the probability of losing money, we make an investment.

Beta is not linked to the underlying business fundamentals and has no use in our analysis.

Outperformance comes from concentration

The only thing we can be certain of, is uncertainty; so a small level of diversification is required. However, too much diversification can increase risk through addition of inferior business models and complexity in portfolio management.

Those that believe they need diversification to cover risk, as is the conventional wisdom, are better served by indexes. The problem is that moving with the herd also means accepting returns no greater than the market average.

Outperformance comes from filtering a large investable universe to identify the very best businesses. By applying a deeper level of analysis, a small number of ultra-high-quality companies will rise to the surface. With a high-conviction strategy a portfolio is not weighted down by diversification.

Once the initial analysis is done, and a position is taken, it requires close attention to maintain performance. All things are in constant flux, an irrational obsession builds a safe harbour.

As Andrew Carnegie said, “It’s trying to carry too many baskets that breaks most eggs in this country. He who carries three baskets must put one on his head, which is apt to tumble and trip him up. One fault of the American businessman is lack of concentration.”

Macroeconomics is unpredictable

When it comes to macroeconomics, and the complex interconnectedness of the world and all its actors, we don’t believe it’s possible to make predictions.

We continually search for great businesses, with able management, selling at attractive prices. When we find an opportunity that matches our criteria we buy it. We don’t attempt to predict market movements.

Markets can suddenly collapse, rocket upwards, or go nowhere for long periods of time without warning. We stay focussed on company fundamentals. Unless there is a material deviation from our original analysis we stay invested regardless of the macroeconomic picture.

Sustainability is a function of outperformance

Companies taking a proactive approach to sustainability outperform the market because being sustainable means being efficient, reducing risk and building brand image.

Excess waste is a cost. Companies reducing waste and pollution improve their margins[2][6][12][13][14].

Happy employees are more engaged. Employees content in their jobs are more engaged and productive leading to improved client relationships and gross margins[3][5][7][9][16][17][18].

Sustainable companies have less risk. Companies that proactively control their impact on the environment and people have a greatly reduced risk of litigation[4][8][11].

Acting responsibly builds brand image. Being a responsible corporate citizen with high standards of ethics improves brand image, builds customer loyalty and reduces cost of client acquisition[1][8][10][15].

Sustainability means making good business decisions. Sustainable companies recognise that waste is a cost, that happy employees maximise net margins and that supporting communities creates loyal customers.

| Myths | Blue Oceans Thinking |

|---|---|

| Value opportunities can be found by looking at low PE ratios. | We do not consider PE values. PE ratios are made up of two erroneous metrics leading to an erroneous conclusion. P, the stock price, likely won’t reflect the true value of the company and E, earnings, comes from net income, a calculation for tax purposes and not actual cash flows from the business. |

| WACC is a critical component of valuation. | We do not use WACC in valuations. Risk is directly related to the drivers of price and volume and not the expected return of investors. Why should their collective expectations necessarily be correct? Why would a small cap growing at 30% p.a. with multiple macro tailwinds represent more risk than a large cap growing at 5% p.a. in an industry undergoing widespread disruption? |

| Beta is a true measure of risk. | We do not use beta in valuations. It is the drivers of price and volume that constitute an investors risk. It is not recent movements in stock price relative to its index or its peer companies. |

| The CAPM is essential in calculating the discount rate. | We do not use the CAPM in our valuations. Our focus is entirely on the individual business performance and not the market its stock price is quoted on. We do not recognise significance in expected stock market return, beta, or the market risk premium. If an investor is concerned about short term market movements they are speculating and not investing. |

| The terminal value formula is correct and an essential part of DCF valuation | Calculating WACC, including beta, on a company today produces a wide margin of error. The calculation estimated many years in the future is nonsense. |

| A portfolio must have at least 30 stocks to be adequately diversified. | Mainstream diversification theory makes exceptional portfolio performance mathematically improbable. Assembling a large portfolio uncorrelated stocks merely creates a replica of the index. We are content in holding 7 – 10 of the best opportunities available and do not follow mainstream diversification theory. |

| A rational investor only holds a portfolio on the efficient frontier. | We do not use efficient frontier theory in managing our portfolio or in making purchase decisions. Levels of variance of expected returns and estimated standard deviations do not combine to provide insight. Our focus remains on the factors concerning the individual business situation. |

| The best talent can be found from the best business schools. | We hire for diversity of thought and intelligence. Mainstream wisdom is taught at all leading business schools and so hiring individuals who have excelled at learning and applying that school of thought would diminish our value not increase it. |

| Be aware of and make provision for black swan events. | Unexpected events can occur at anytime causing dramatic market movements and that does not concern us. We stay focused on the performance of businesses in our portfolio and searching for new opportunities. Macro events rarely impact the trading conditions of businesses we own and the effects on their share prices are temporary. |

| Rebalancing reduces risk through diversification. | We don’t rebalance to achieve diversification, we’ve comfortable with our conviction. We don’t believe that Our tolerances are for a much more concentrated portfolio and we allow stocks to grow larger portions of the overall portfolio than mainstream would allow. The risk is in the business model, if that business model is performing exceptionally well we continue to hold our position. |

| Pick an industry that is likely to outperform and buy the best stocks in that industry. | We choose stocks, not sectors. When looking for new investments we scan every company on global listed exchanges. In that way we know which companies have the best performing business models and we are not attempting to choose an individual industry or sector. |

| Buy into cyclical stocks at the bottom and sell them at the top (buy low, sell high). | We do not invest into cyclical business models. Frequent trading produces a large tax burden. Timing entry and exit points cannot be done accurately over long time-scales. Commodity industries are prone to complex factors making estimations of future cash flows void. Commodity industries usually do not align with sustainability. |

| If a company misses guidance, sell it. | Guidance in our view is unnecessary and prone to error. We would rather see managers managing a company to current conditions, not investor expectations. |

| If a company misses analysts expectations, sell it. | The opinions of analysts are irrelevant. |

| Small caps hold greater risk than large caps and should be valued accordingly lower. | We do not believe small caps hold more risk than large caps simply because they are smaller. We analyse the risk of small caps and large caps in the same way. |

| A capital raising increases valuation. | A company’s value is its ability to generate cash flows and not its popularity amongst investors. |

| Companies can be grouped into sectors and good diversification is spread amongst multiple sectors reducing risk. | The concept of sectors is irrelevant to us. Apart from our sustainability criteria we are sector agnostic. Diversity amongst business models in the same sector is immense. |

Inspired by these great thinkers

You must decide for yourself what is true. Learn from others to develop knowledge, use that knowledge with your creativity to find your own truth.

References:

- Aragon, A., Makarova, E., Ragani, A.F., Rutten, P., 2017. “Manufacturing quality today: Higher quality output, lower cost of quality.” McKinsey & Company.

- Beal, D., Lind, F., Young, D., 2019. “What companies can learn from world leaders in societal impact.” Boston Consulting Group.

- Buckingham, M., Goodall, A., 2019. “Engaging employees.” Harvard Business Review.

- Bower, T., 2020. “Why boards should worry about executive’s off-the-job behavior.” Harvard Business Review.

- Creary, S.J., McDonnell, M.H., Ghai, S., & Scruggs, J., 2019. “When and why diversity improves your board’s performance.” Harvard Business Review.

- Eccles, R.G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G., 2014. “The impact of corporate sustainability on organisational processes and performance.” Journal of Management Science.

- Guver, S. & Motschnig, R., 2017. “Effects of Diversity in Teams and Workgroups: A Qualitative Systematic Review.” International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology. Vol 7, No 2.

- Henisz, W., Koller, T., Nuttall, R., 2019. “Five ways ESG creates value.” McKinsey & Company.

- Hunt, V., Lareina, Y., Prince, S., & Dixon-Flye, S., 2018. “Delivering through diversity.” McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/delivering-through-diversity

- Laubli, D., Ottink, N., 2016. “The quest for quality in fresh-food retailing.” McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-quest-for-quality-in-fresh-food-retailing

- Puri, S., 2019. “Your star salesperson lied. Should he get a second chance?” Harvard Business Review.

- Porter, M.E., Van Der Linde, V., 1995. “Green and competitive: Ending the stalemate.” Harvard Business Review.

- Rubel, H., Schmidt, M., Meyer zum Felde, A., 2017. “The urgency – and the opportunity – of smart resource management.” Boston Consulting Group.

- Stuchtey, M., 2015. “Rethinking the water cycle.” McKinsey & Company.

- Takeuchi, H., Quelch, J., 1983. “Quality is more than making a good product.” Harvard Business Review.

- Vadnai-Tolub, G., 2019. “More than work-life balance, focus on your energy.” McKinsey & Company Organisation Blog. Retrieved from: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/the-organization-blog/more-than-work-life-balance-focus-on-your-energy

- Whillans, A.V., 2018. “Time poor and unhappy.” Harvard Business Review.